Dear friends, welcome to another video pitfalls pill! Today’s post concludes our mini-series about using the “best possible evidence.” In the previous weeks, we always assumed you had control from the beginning. Today, we focus on a different yet widespread scenario: you receive the video “evidence” from someone else and are asked to work on that. Want to know the undercover pitfalls in this situation? Just keep reading!

Issue: Did You Get the Right Data?

In the past few weeks, we’ve been showing the pitfalls hidden in some bad habits related to video evidence handling: we’ve seen why you should not film a display, why a DVR’s proprietary player is usually not very trustworthy, and why you should avoid using a screen capture tool. In all those posts, you were the main actor, and you could decide what to do. But what if you’re called on the phone by a colleague or, worse yet, by your boss, and asked to “work on the video I’m sending you”, since “we urgently need the license plate”?

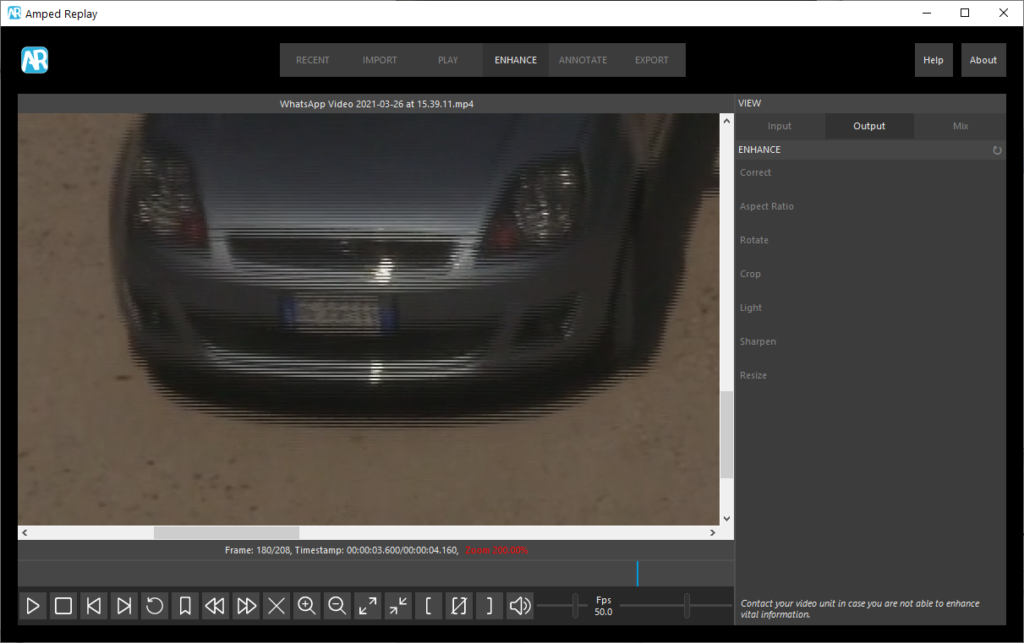

After a few moments, you receive a Whatsapp message with the video. You bring it into your workstation, and it looks like this.

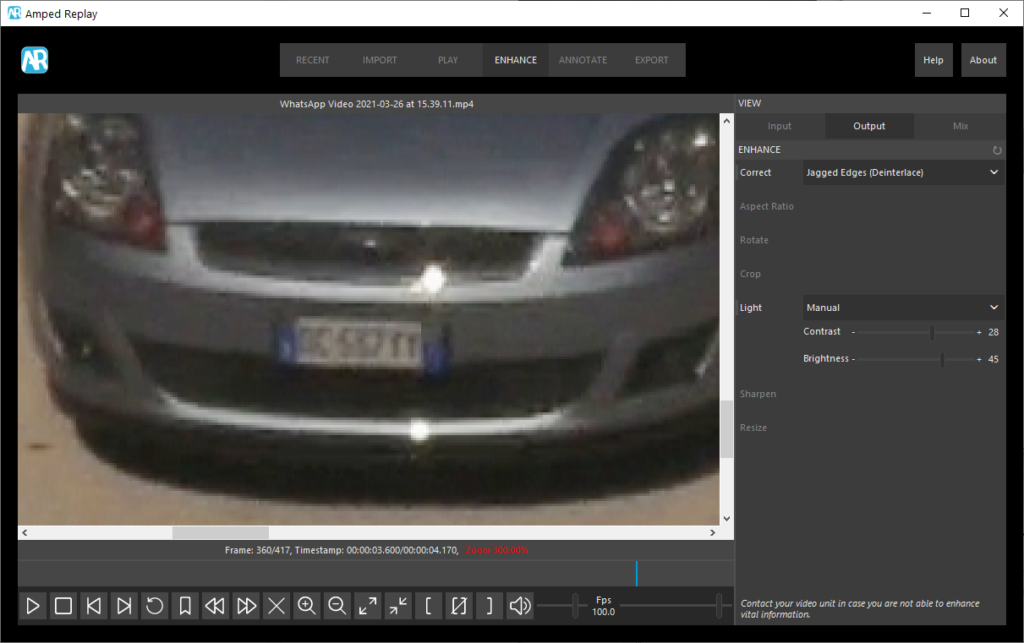

You promptly notice that Deinterlace is needed, which is one click away with Amped Replay. After the deinterlace, and some tweaking with Lights, you have this.

Which is better, though not great, but wait. Deinterlace? And the video came from Whatsapp? That means the video was probably recompressed before being deinterlaced. Which is obviously suboptimal (fields get mixed together by compression). And then, how did your colleague get the video into Whatsapp? Did they film the video? Did they screen-capture it and used Whatsapp Web?

You are slowly realizing that there are too many things you don’t know. This brings up two problems:

- The work you’re doing can perhaps be used for a quick check, but then you will have to redo everything from scratch. Delivering a video exhibit via Whatsapp? That’s good for a joke!

- Even the “quick check” could be severely affected! With a video like the one above, you may manage to read a couple of characters. But what if you had the original? Maybe you could have read much more! It is fundamental that your colleague/boss get this point right.

Explanation: Most Actions Will Degrade Your Evidence

Images and videos are discriminated against. They are treated differently than other digital documents. When you send a text document via email, Whatsapp, Telegram, or whatever messaging system, you are sure it will be delivered as it is. None of these services would ever dream of “cutting some unnecessary sentences”, or “reformatting the document to save space”. Well, with images and videos, that’s what they do most of the time.

Sending a video via Whatsapp will normally cause it to be downscaled and recompressed. The same happens with most messaging systems. That means, you lose quality and you lose integrity, which makes the video unfit for forensic purposes and less useful, or even useless, for investigative purposes.

As we said in the past, we can’t blame messaging systems for doing so: if they would send the original, you would consume your whole data plan in two weeks, and fill your smartphone storage in two months. The problem is on your (colleague’s) side: messaging systems are not the way to send multimedia evidence when some important action (such as reading a license plate) depends on it. In such a case, you need to have control of the initial acquisition, or at least to have full documentation of it, for all the reasons we’ve explained in the last weeks, which can be summarized in: you want to access the original pixels.

Unfortunately, things are not going in the right direction. Several law enforcement agencies are encouraging citizens to proactively “provide recordings of events” to help investigations and to do so by “uploading to our web page”. But once you get such footage, how do you know its acquisition process? If it has been exported from a CCTV system, how did they export it?

To make things worse, some modern “cloud-based” surveillance systems will export different data based on how you access them. If you download it from the web panel, it will be one quality. If you access it via a smartphone app, it will be another quality. And this is not even the worst we have seen. We have received requests to enhance screen capture snapshots pasted into Word documents and given as “the only file we have”, photos for comparison sent via fax, and requests for a forensic analysis of digital image files’ printouts (without the file itself). These are all against what we preach in this and the previous posts.

Solution: Ask For the Original

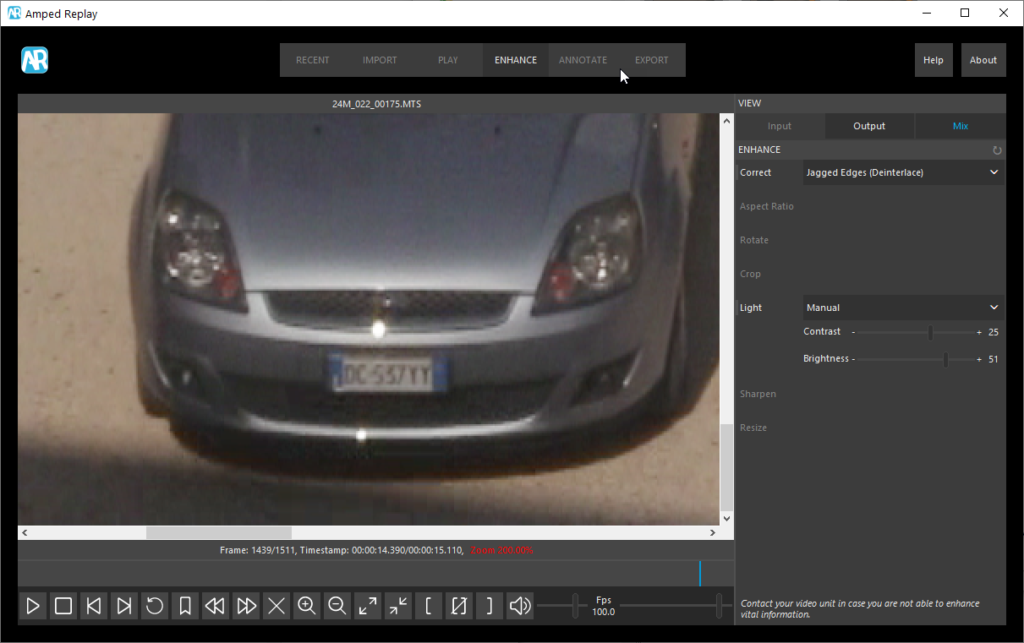

As simple as it seems, “asking for the original” is the key. Let’s go back to our initial example. If we had access to the original video, we could apply Deinterlace to the original pixels, obtaining this.

As this example shows, working with the original can make all the difference.

When “classical” surveillance systems are considered, it’s quite easy to guess whether your exhibit is something different from the original: if the footage comes in a standard format, it has likely been transcoded, converted, or somehow captured. That should trigger your alarm and raise the question: is this the original recording? How did you get it? Can I have the acquisition report for this? If there’s no such report, how am I supposed to start a proper chain of custody? It’s better if you ask these questions, before being asked in court!

Keep in mind that a case may appear “quick and easy” at the beginning, and then get serious as time goes by. Unfortunately, time is against you: if you don’t get the original today, tomorrow could be too late. Surveillance systems continuously overwrite footage with new recordings; in some places, the jurisdiction itself asks the owner to wipe recordings every two days or so.

If video evidence is provided by a citizen, try to gather as much information as possible about when it was captured and how it has been acquired/exported. If you get only the pixels, how will you be able to answer questions about the reliability and authenticity of such an exhibit?

We hope that, as simple and limited as they are, these weeks’ posts have clarified the importance of working with the best possible evidence. Spread what you’ve learned to your colleagues, and we’ll hopefully build together a better forensically sound world!