Dear friends, welcome to your weekly dose of fear! Starting from today, we’ll be addressing a fundamental issue, perhaps the most important in your video forensic workflow: using the best possible evidence. We’ll dedicate some posts to this important topic, covering the various pitfalls you may encounter. Today, we’ll see why using a mobile phone (or even a professional camera on a tripod) to capture footage is, well, not recommended. Cell phone snaps come with bad quality and reliability. Keep reading!

Issue: Filming the Display Creates Awful Footage

Let’s start with a quote from one of our esteemed users:

The jobs I manage never get that far as we work with appalling quality footage in the vague hope of securing a conviction.

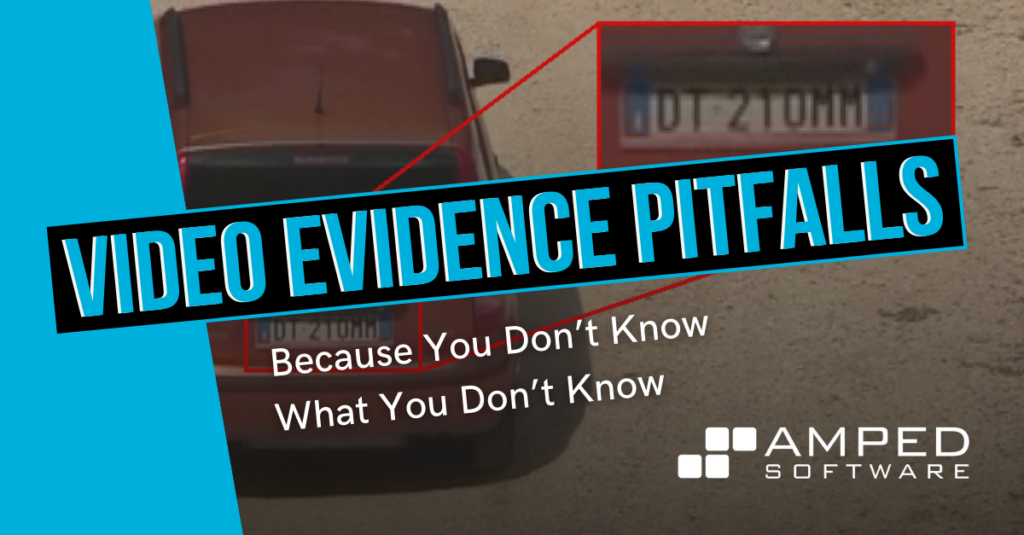

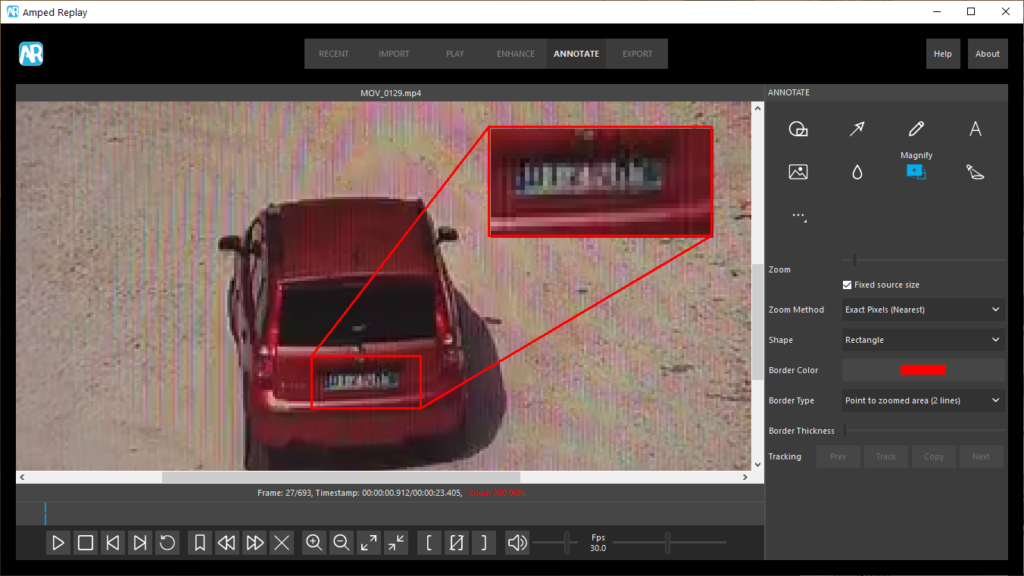

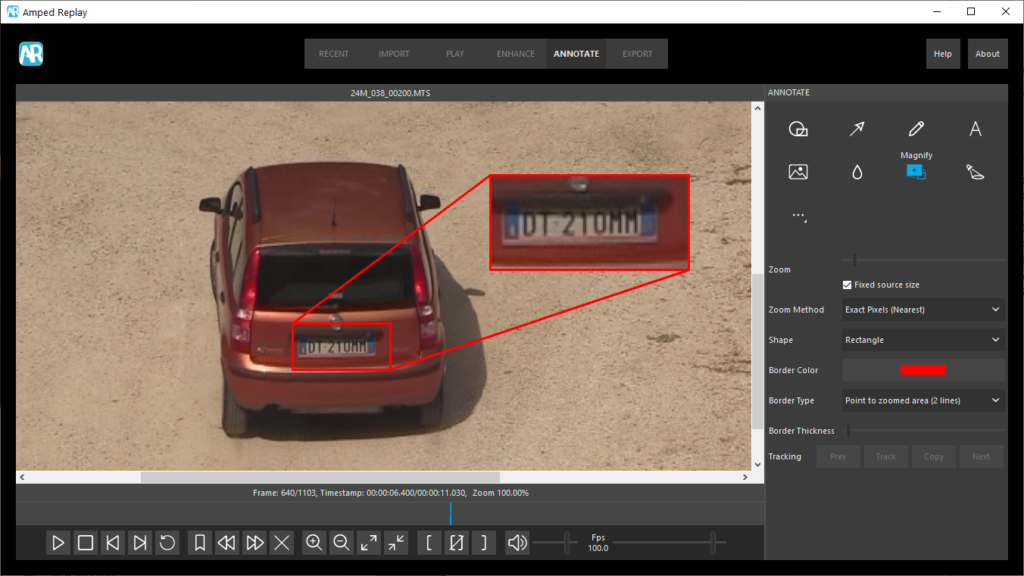

Well, it’s certainly true that, sometimes, there’s not much we can do. But in many cases, the “appalling quality” is due to how the evidence video has been acquired, or how the working copy has been produced. Let’s go practical with an example. Can you get this license plate?

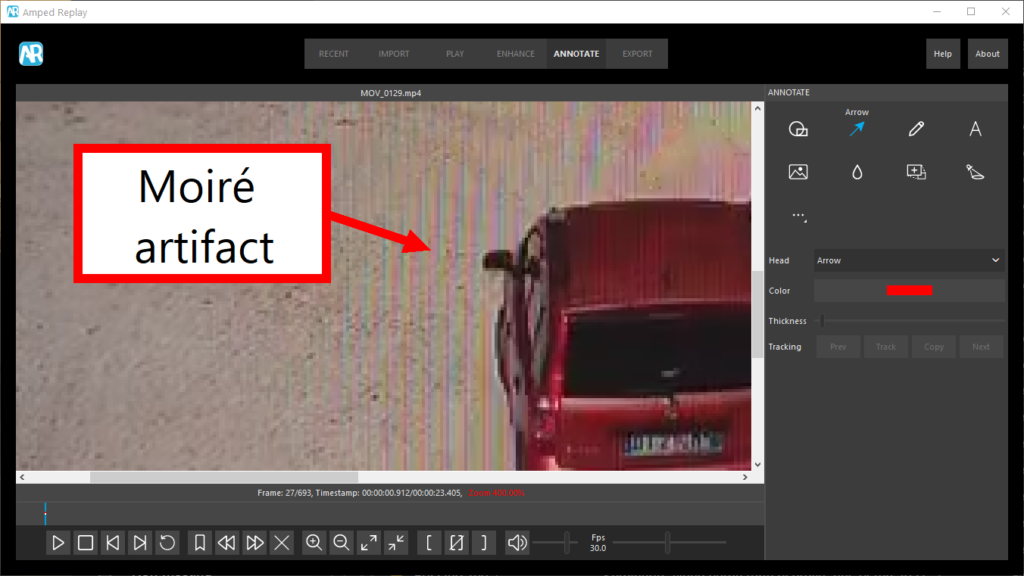

What you see above is the typical result of filming a display with a smartphone while the video plays. It’s horrifying, I know, you’d never do that, but, many people actually do that! This is how the original video would have looked if it was properly acquired.

I’m sure these pictures speak for themselves! “But hey”, you may think, “I have a super-recent smartphone with 4k video @60fps, I wouldn’t lose that much!”. Trust me, you would. Let’s see why.

Explanation: Interference, Loss of Definition, and Compression Kill Quality

Videos are ubiquitous in our everyday lives. This probably explains why many people tend to think “video is just video, anyone, any software, or any system can handle that, just like you would be able to view and share a PDF document”. Well, perhaps it’s true for your holiday pictures, but not for evidential footage. There are several common mistakes that can negatively impact both the quality of your exhibit and the integrity of your chain of custody. Whenever you do something with your evidence, you need to understand the possible consequences of it.

Now, taking a picture or filming a display is probably the worst thing you can do. You obviously lose pixel definition in most cases, since the digital signal goes back to the analog domain for viewing. Then it’s digitized and compressed again by your camera. Frame timing accuracy will also be affected, since the player and your camera likely have a different frame rate. Even if they are the same, they’ll hardly be in-sync and you may lose or duplicate lots of frames. Besides that, you’ll likely be introducing the very annoying Moiré artifact, which is explained in another post. It is principally caused by the interference between the pixels grid of the display and the pixels grid of your camera sensor. This issue was indeed very evident in the first picture of this post.

Finally, you will of course lose all the properties and metadata embedded in the original video, since you’re creating a brand new digital file that, technically speaking, does not share ANYTHING with the original exhibit.

All of this has several implications, for example:

- it will be extremely hard to know if you’re playing the video at the correct speed;

- if you can’t see/read something, you are left with a Kafkaesque doubt: “would it have been visible if I had used the best possible evidence instead?”

- it may be fairly simple to prove the authenticity of a cell phone snap or video through the chain of custody, but it will be impossible to prove integrity. The image or video has changed significantly since the time of acquisition and it will be up to the opposing legal team to argue that this lack of integrity should result in the inadmissibility of the evidence.

Solution: Stick to a Forensically Sound Workflow

Although we stigmatized taking pictures of the display, we understand it’s a method that can have its place. You may need to take a quick snap of the player with your smartphone to quickly get it to the field while investigating with your colleagues if time is critical.

But remember that is not your evidence. After you have done the “quick and dirty” job you need to secure the actual evidence. Be prepared for a proper acquisition and analysis later.

It’s not just a matter of “better results”. When you don’t acquire, or export, or copy a video properly, you’re creating a new exhibit that is unjustifiably different than the original piece of evidence. It is NOT the best possible evidence. You really don’t want to find yourself in a courtroom trying to justify this.